Summer is slowly fading, but there’s no way we’re putting our favorite pieces away just yet. Thanks to layering from the English word for “layers”, we can extend the season. A closer look at a style that blends 2000s heritage with today’s unpredictable weather.

Layering: between necessity and social construct

Before it became a fashionable term, layering was above all a necessity: to survive winter, people had to cover up. Long before technical fabrics and heat-regulating materials, it was the layering of clothes that kept body warmth in. Layers were not only protection against the cold but soon also signs of social identity.

Throughout history, especially among the privileged classes, these successive layers took on a meaning that was less practical than symbolic. For women in particular, the ritual of dressing was a true performance. Undergarments were already considered full-fledged garments. On top came the corset, then the dress, sometimes accompanied by an overdress. This process was anything but trivial: it could not be done alone. Assistance was required to put on these multiple layers, a sign of social status, certainly, but also a form of dependence.

And of course, being corseted restricted movement, constrained posture, and limited breathing. Layering thus became a tool of control, a way of imposing norms on the female body. Far from the sense of freedom we associate with layering today, it was at the time a strict code, one that revealed underlying power dynamics.

Extending summer, layer by layer

Times have certainly changed. Today, layering is mostly about fun. We look for ways to wear our favorite summer pieces for as long as possible. As autumn approaches, that slip dress once worn on its own now pairs with jeans and slips under a cozy sweater. And when the sun breaks through the clouds, off comes a layer. Which one? That’s up to you.

Another example of summer adaptation: the sarong, that light accessory still carrying a hint of sunscreen. Instead of putting it away until the next holiday in the sun, it’s worn around the hips, as a skirt or an overskirt. The result: an asymmetrical silhouette, both fluid and structured. Content creator Pauline Leroy has recently made it her signature, playing with contrasts and volumes without ever weighing down the look.

A heritage straight from the 2000s

It’s impossible to talk about layering without going back to the 2000s, that emblematic decade when piling on clothes was almost the norm. On the red carpet, Disney icons like Ashley Tisdale, unforgettable as Sharpay Evans in High School Musical, combined low-rise jeans, sequin skirts, cascading T-shirts, flashy accessories, and eye-catching ballet flats. Back then, the more the better. And while trends are cyclical, that overloaded aesthetic has evolved.

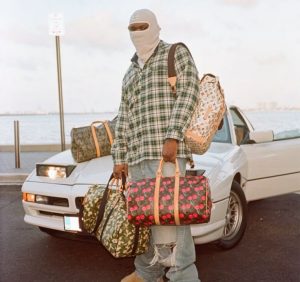

Today, layering takes two distinct approaches. On one side, those who seek harmony: a coherent silhouette built from timeless pieces in neutral tones, where the element of risk remains measured. On the other, the contrast lovers, in a spirit clearly inherited from Y2K, who mix fabrics and colors without shying away from bold clashes.

Whichever approach you take, it all starts with a solid base: a well-chosen essential, a structured blazer, flowing trousers, or an asymmetrical dress that serves as the anchor. From there, it’s up to each person to build a sophisticated monochrome silhouette or venture into a perfectly orchestrated explosion of colors and textures

Layering, far from being just a mid-season trick, reveals much more than aesthetic concerns. Historically used to keep out the cold or to signal social status, it is now reclaimed as a tool for storytelling, even emancipation. Because stacking layers also means telling a story: of a garment repurposed, a fabric recycled, a summer memory slipped beneath a winter jacket. It’s about playing with volume, blurring codes, and rejecting the linearity of a fixed silhouette.

In its contemporary form, layering does more than keep us warm. It mirrors our relationship with clothing today: multiple, shifting, and just a little political.