Since 2004, H&M has been bringing luxury closer to the public through collaborations with prestigious designers. These short-lived, highly publicized collections make it possible to wear pieces normally reserved for the runway. But behind the glamour, the industrial reality is far less dazzling. Why do these designers agree to collaborate with fast fashion?

H&M, the fast-fashion giant and undisputed master of collaborations

H&M is the only fast-fashion player to have collaborated with luxury designers for more than twenty years. As early as 2004, the brand began releasing one collection a year signed by a renowned designer. A concept that has completely transformed the relationship between luxury and the public and vice versa.

The first resounding success? The Karl Lagerfeld collection, which sold out in just a few hours, even though the stock had been planned to last several weeks. Since then, major names have followed: Roberto Cavalli, Comme des Garçons, Sonia Rykiel, Versace, Marni, Maison Martin Margiela, Isabel Marant and Balmain, among others. H&M’s goal is simple: to make the creations of top designers accessible.

To celebrate twenty years of collaborations, the brand even put back on the market select pieces sourced from second-hand platforms, a sign that these collections retain both symbolic and commercial value long after their release.

Glenn Martens, always faster

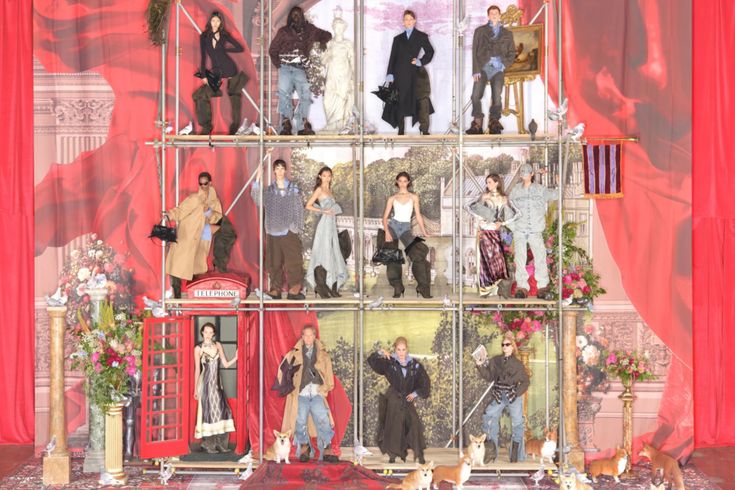

In 2025, Glenn Martens and Ludovic de Saint Sernin are collaborating respectively with H&M and Zara, the two biggest fast-fashion giants alongside Uniqlo. For these designers, such collaborations offer instant global visibility and a way to reach consumers who would never have been able to access their original collections.

Behind the marketing success, production conditions remain far removed from those of luxury houses. Factory workers on the other side of the world are the ones who feel the impact first. Raw materials are rarely high-quality, the production pace is frantic, and the result is often short-lived: a garment that survives only a few washes or its owner’s boredom. On Reddit, a user commenting on the Glenn Martens x H&M collaboration even remarked: you’d be better off buying second-hand Y/Project,’ referring to the designer’s former label, now closed.

This year, the Belgian designer is everywhere: he has been appointed artistic director of Maison Margiela while continuing his work at Diesel. The collaboration with H&M adds yet another commitment to an already overloaded schedule. But did he really need this collaboration? The question goes beyond Martens himself and reveals a broader phenomenon: a fashion industry that is accelerating relentlessly. Today, a designer deemed ‘essential’ is often one who juggles several creative directions, multiplies projects, and moves between luxury, streetwear and fast fashion. The pace isn’t just fast; it has become mandatory.

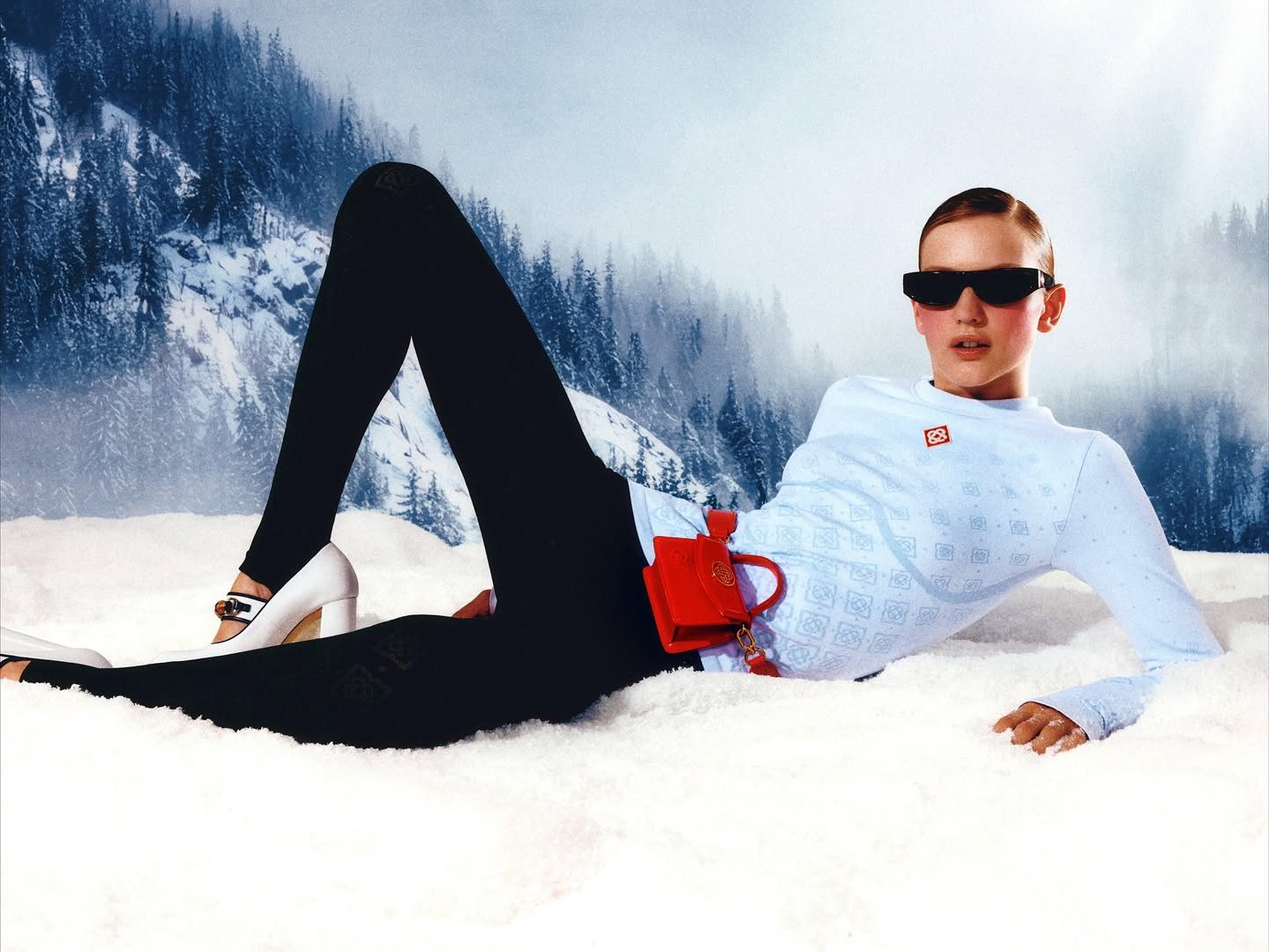

Zara bets on fashion’s new enfant terrible

In just one year, the Belgian designer has pulled off a true split: he created the Jean-Paul Gaultier couture collection in January, then collaborated with Zara in November. After a brief stint, just one season as artistic director of Ann Demeulemeester, Ludovic de Saint Sernin now seems to move fluidly between several worlds, from the most cutting-edge to the most commercial.

Zara, for its part, is continuing its transformation. In recent years, the brand has refined its image: its stores now offer an almost premium shopping experience, its collections capture trends at record speed, and its prices have risen considerably as a result. The launch campaign for the collaboration, filmed in the streets of New York, features models who are omnipresent on the runways. The result: it becomes difficult for the public to realize they’re looking at fast fashion. And this is precisely where Ludovic de Saint Sernin comes in: he brings Zara the extra touch of ‘luxury’ legitimacy the Spanish retailer was missing.

At the core, collaborations between designers and fast-fashion brands reveal a deep contradiction: they create the illusion of more accessible luxury, while relying on a model that remains unchanged. Designers gain global visibility, brands acquire a prestigious aura, and the public gets the chance to purchase a signature piece. But this supposed democratization hides the flaws of a well-functioning system: quality often sacrificed, unbearable production rates, and difficult working conditions.

So why continue collaborating with fast fashion? Because in a saturated market, these partnerships have become both a visibility tool and an economic lever. Because luxury now seeks its audience everywhere. Because fast fashion, for its part, has long been searching for a veneer of legitimacy.